Avoiding Failure in Finish: Common Hot-Dip Galvanizing Mistakes That Separate Quality Manufacturers from the Rest

Hot-dip galvanizing is widely regarded as one of the most reliable and cost-effective methods of protecting steel from corrosion, especially in harsh environments. When done correctly, it ensures decades of durability and low-maintenance performance. However, the process is both chemistry and process sensitive. Even minor lapses in quality control can lead to coating defects, product rejection, and expensive rework; often discovered only at the final stages, or worse, on the customer’s job site.

While many manufacturers claim to offer galvanized products, only seasoned, process-oriented facilities understand and respect the technical depth involved. In this post, we explore the often-ignored but crucial galvanizing mistakes that signal poor manufacturing practice, and how true quality-focused manufacturers mitigate them.

1. Surface Preparation: The Unseen Foundation of Quality

The integrity of hot-dip galvanizing begins long before the steel is dipped into molten zinc. Surface cleanliness is absolutely critical. Steel surfaces contaminated with oil, grease, mill scale, rust, or welding flux residues will not allow zinc to properly metallurgically bond with the substrate. In such cases, the result is either poor adhesion, peeling, or completely uncoated patches, defects that are both visually obvious and structurally compromising.

High-quality manufacturers understand that surface preparation is not a one-size-fits-all process. They tailor degreasing, acid pickling, and fluxing treatments depending on the steel type, storage conditions, and fabrication method. Poor-quality manufacturers often skip degreasing or rely on overused chemical baths, which dramatically reduce process reliability. What differentiates a seasoned plant is not just the availability of cleaning tanks, but the discipline to maintain solution concentration, temperature, and replacement cycles with precision.

2. Fabrication Practices That Hinder Galvanizing

Welding plays a vital role in most steel fabrication, but poor welding practices can render an otherwise perfect galvanizing line useless. Residual flux, welding slag, and non-ground weld beads create barriers to zinc adhesion, leaving voids in the coating. Additionally, steel components with sealed sections or improperly vented cavities can trap air or moisture. This not only prevents uniform coating but also poses serious safety risks during dipping, sometimes causing zinc splash or even explosion due to trapped steam.

In a quality-oriented facility, fabricators are trained in galvanizing-conscious welding, which includes the use of low-silicon electrodes and post-weld cleaning. Designers collaborate with galvanizers during the early product development stage to ensure drainage and vent holes are appropriately placed. These may seem like small details, but they define whether a product comes out of the zinc bath flawless or needs to be scrapped.

3. Steel Chemistry: Why It’s Not Just About the Grade

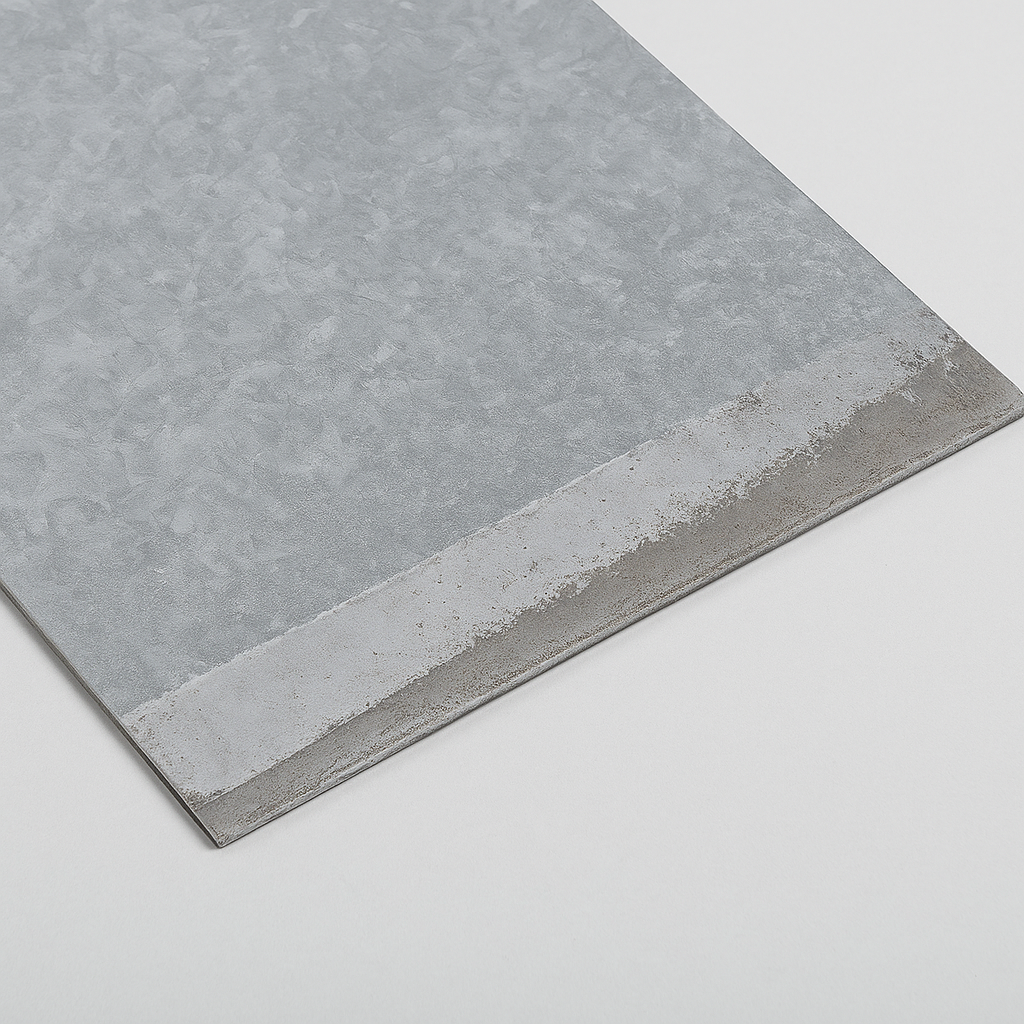

Many inexperienced or cost-cutting manufacturers treat galvanizing as a standard post-process, without considering the chemical composition of the steel itself. This is a serious mistake. Steel with high silicon or phosphorus content reacts aggressively with zinc, often forming excessively thick, brittle coatings that are rough, dull grey, and prone to flaking. This phenomenon, known as the Sandelin effect, is particularly common in steels with silicon content between 0.05% and 0.12%.

To avoid this, expert galvanizers request material test certificates (MTCs) from steel suppliers and work only with silicon-controlled steel grades. Steels within the optimal silicon range (usually 0.02–0.06%) allow for controlled zinc pick-up and smoother surface finish. While this requires more planning and higher input costs, it ensures products meet international standards such as ISO 1461 or ASTM A123 with consistency.

4. Temperature and Immersion Control: Precision That Can’t Be “Eyeballed”

Molten zinc baths operate at around 450°C, and even slight fluctuations in temperature or immersion time can affect the structural and aesthetic quality of the final product. Over-dipping can lead to excessive coating thickness, especially at corners and edges, resulting in a lumpy or crystallized surface. Under-dipping, on the other hand, may produce weak adhesion and incomplete coverage, both reasons for customer rejection or performance failure in the field.

In poorly managed facilities, dipping is often manually timed by operators with little more than visual judgment. In contrast, professional galvanizers use automated hoists with programmable logic control (PLC) to precisely control dipping cycles based on the steel’s surface area, thickness, and geometry. This ensures repeatability, uniformity, and compliance with strict coating thickness specifications.

5. Product Design That Fails in Practice

Another critical error- more common than one might expect is when the product’s geometry is inherently unfit for galvanizing. Closed boxes, flat horizontal planes, and small hollow sections without proper venting cause zinc to pool, trap air, or flow unevenly. This leads to sagging, drips, and uneven surface texture. Aesthetic issues aside, pooled zinc also adds unnecessary weight, creating handling and cost problems.

Experienced manufacturers involve design engineers at the earliest stages. They consider galvanizing suitability as part of the design review, ensuring correct placement of vent and drain holes, sloping surfaces, and accessible inner voids. These small modifications can prevent major coating defects and reduce zinc consumption.

6. Post-Dip Handling: The Final, Often Ignored, Step

After a successful dip, the product is still vulnerable. If post-dip handling is rough or rushed, the freshly galvanized surface can be scratched, contaminated, or marred by oxidation. Worse, if excess zinc isn’t properly drained or brushed off, sharp burrs and spikes may remain, posing a safety hazard and making the product unsuitable for export or consumer use.

This stage requires care, trained personnel, and sometimes mechanical finishing. Components are either spun (for small parts) or manually brushed to remove drips. They are cooled under controlled conditions to avoid sudden stress. Unfortunately, many low-end suppliers treat this as a mere packaging step, rather than a critical quality control phase.

7. Final QA: Where Poor Shops Cut Corners and Reputations Suffer

Even if every upstream process is performed correctly, skipping final QA can render it meaningless. Galvanized parts must be inspected for coating thickness, uniformity, adhesion, and appearance before they are shipped. Products destined for European markets must conform to EN ISO 1461 or country-specific regulations, which require documented proof of compliance.

High-end suppliers deploy coating thickness meters, gloss meters, and destructive testing protocols where applicable. Each batch is traceable via serial numbers, heat codes, and dip records. This level of documentation not only prevents disputes but also positions the supplier as a credible partner for large-scale retailers and infrastructure projects.

Galvanizing Is a Science, Not a Shortcut

Hot-dip galvanizing doesn’t simply mean dipping steel in zinc. It’s a highly engineered process that requires metallurgy knowledge, precision process control, and production discipline. Manufacturers who treat it as an afterthought are not just risking product failures, they’re risking brand trust.

At GKG Industry, our hot-dip galvanized products are produced in a certified environment under ISO standards, using carefully sourced steel and tightly controlled line parameters. We don’t cut corners, and we don’t ship defects.

If your projects demand galvanized products that consistently meet international standards and are ready for retail or site use, we invite you to get in touch with our technical sales team.

Write to us at sales@gkgindustry.com to request our product catalogue or discuss your sourcing requirements.

Author